AUSTIN, TEXAS — The concept of locating similar types of commercial real estate uses in close proximity to one another to allow those users to naturally develop synergies — clustering — is an age-old practice in certain asset classes like office, retail and hospitality. But the strategy can make sense for industrial real estate as well, especially in a time in which new subcategories of industrial uses are attracting capital and generating demand for space.

Logistics and distribution users, for example, typically identify transportation costs as their top line item on the expense side of the ledger. Those companies have little choice but to pay top dollar for land or space near the rooftops of their existing customer bases so as to minimize transit costs.

Editor’s note: InterFace Conference Group, a division of France Media Inc., produces networking and educational conferences for commercial real estate executives. To sign up for email announcements about specific events, visit www.interfaceconferencegroup.com/subscribe.

Data center users cannot properly and profitably function without access to cheap electricity, hence the ability of Texas to land many of those deals via its deregulated power grid. Suppliers of smaller industrial parts and components are often supported by a handful of major manufacturers, and proximity to the “mother” facility is equally key to reducing their overhead costs.

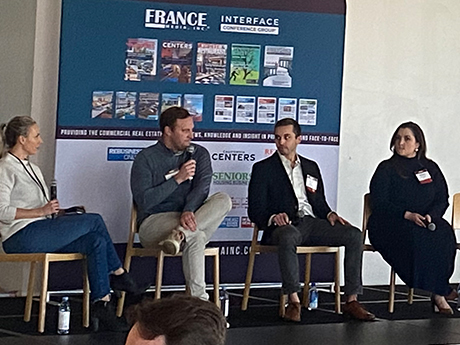

At the inaugural InterFace Austin Industrial conference, which took place earlier this year at The Line Hotel in the state capital’s downtown area, Bryan Baynton, director of acquisitions and development at regional owner-operator Titan Development, gave an example of clustering that’s currently unfolding in Central Texas. He pointed to the city of Lockhart, where Titan recently broke ground on a 60,000-square-foot building, as a good example of a market in which a cluster has been established around a key industry: food.

“Lockhart has done a great job marketing and recruiting consumer products and food-related companies,” he said. “Hill Country Foodworks recently signed a lease, and there’s the Ziegenfelder popsicle facility right next to Titan’s building. But the market really has those suppliers for food-related companies and within that sphere of influence, the competitors all know each other, which can actually be good.”

According to the Lockhart Post Register, Hill Country Foodwork’s new building is 48,900 square feet and is located less than two miles from its main production facility. The publication noted that this proximity allowed the company to “vastly improve process flow and handling of materials and finished product. Additionally, the increase of refrigeration space helps facilitate the millions of pounds of fresh produce processed annually.”

Ziegenfelder announced its $46 million manufacturing facility in Lockhart in September 2022 and held a formal groundbreaking ceremony in spring 2024. The facility, which was forecast to employ about 100 people, is now operational.

Clustering Up

The Austin industrial market remains less mature than those of other major cities, even as the city’s paces of employment, population and housing growth have skyrocketed in recent years. Owners of industrial sites or facilities in this market are pushing outward — a telltale sign of market maturation — and in doing so, creating clusters and nodes that support specific industries, both consciously and by happenstance.

Innovation Business Park, Titan’s 172-acre development in Hutto is a prime example of industrial clustering in the greater Austin area. Titan launched Innovation Business Park with a 72-acre first phase in 2017 and followed that up with the 100-acre second phase in 2021, ultimately yielding more than 1 million square feet of space across nine buildings. Over that stretch, the company has inked deals with users that provide products and services — technology, automotive, infrastructure — that are instrumental to the overall development of the suburban community. Some of those tenants include:

- Global automotive parts supplier Seoyon (212,862 square feet)

- High-value equipment warehousing group EDC Moving Systems (95,000 square feet)

- Door machinery manufacturer Kval Inc. (52,500 square feet)

- Water purification and wastewater treatment firm Ovivo Inc. (110,000 square feet)

Whitney Williamson, vice president and market officer at Prologis, also stated that her company, the largest industrial owner in the world, endorsed clustering as a viable approach for successful development and leasing. Essentially, the strategy pays dividends when tenants need to renew and/or expand into bigger spaces.

“If you look at our Austin portfolio, it’s very much concentrated around a certain area,” she said. “The reason for that is that a lot of our customers need to be close to specific vendors and suppliers, as well as rooftops. When they scale with us from 50,000 to 100,000 square feet, they still want to stay in those areas. So clustering [our properties] allows up to support that growth as much as possible.”

Otto Swingler, co-founder of Austin-based investment firm Balcones Real Estate Group, then shed some light on how deliberate clustering can unfold.

“We’ve been fortunate to take down larger land positions, buying at scale, master-planning and developing it out in phases to create very small submarkets,” he explained. “By doing that, you create a campus-like feel that groups want to be part of. That’s given us conviction to move forward with new buildings as we’ve rolled out those programs.”

Panel moderator Amber Autumn, director of business development at Summit Design + Build, then concluded the discussion by noting that tapping a cluster on the front end often pays dividends on the back end.

“From a general contractor’s perspective, it’s great to work in clusters, because if you land one project, chances are you’ll get introduced to another one nearby,” she said. “In Chicago, we rolled out a Vienna hot dog factory and then got introduced to Alpha Baking, which makes the buns for the hot dogs. Then we did a project for a relish company.”