By Tyler Hague, Colliers

A colleague of mine recently had to move out of her West Loop apartment quickly and she faced a conundrum: how much am I willing to pay for a one-bedroom apartment in Chicago? The unfortunate answer: not even close to the $2,700 per month rent she was continually being asked to pay. She ended up renting a studio.

The average price for a one-bedroom apartment in the central business district is $2,478 per month, a figure that has grown 9.5 percent in the last year alone and equates to a $235.41 year-over-year rental increase, according to Yardi Matrix.

It also translates to a national housing insecurity crisis, not just a local and presumed urbanized problem, and one that has been exacerbated by many of the detrimental housing laws and zoning regulations that exist in Chicago today. Whether it is aldermanic privilege, the Affordable Requirements Ordinance (ARO) or general NIMBYism, it is clear rent is too darn high — and it isn’t the entrepreneurial real estate professional’s doing but rather a major (and obvious) supply dilemma.

This summer, for the first time in U.S. history, median rent costs in major cities surpassed $2,000 per month, according to a Redfin report issued in May. Rent has surged by more than 30 percent in places like Seattle and Cincinnati and over 48 percent in Austin, the largest increase in a metro area in the U.S. Even cities previously known to be “affordable” have seen their rents grow 20 to 30 percent with the lack of supply being the biggest force pushing up housing prices.

The trend has been evident in the Chicago metro area too, although the market lags other markets by several months and percentage points with year-over-year growth coming in around 13 percent for the city and 22 percent for the suburbs, according to Yardi Matrix.

Demand for housing, and in particular rental housing, has grown increasingly in the wake of the Great Recession where demand for apartments consistently increased and the supply of new housing plummeted. For decades, many of the policies that have been used to address the complexities of the housing crisis in Chicago have focused on inadequate, underfunded and superficial housing policies that appeal more to garnering votes than creating real solutions.

Politicians go for the quick and easy talking point policies instead of creating real, meaningful policy reform that will generate the housing the area needs. What we are left with is skyrocketing rents and rushed policies like the ARO, coupled with aldermanic privilege and NIMBYism, that have added to the cost of housing, not reduced it.

Supply shortage causes

So, how did we get here? Over the past few decades, there have been two notable trends in Chicago (with one of them recently being reversed). One, the demolition or conversion of neighborhood two- and three-flats to make way for large, urban mansions; and two, the conversion of apartments to condominiums in the condo conversion craze of the 80s, 90s and early 2000s. Things got so bad that a committee was formed in 2007 to address condo conversions and their impact on tenants after 4,000 apartments in the city were converted to for-sale condos in 2005.

Fast forward 15 years and the condo deconversion craze has taken over as the negative effect on the market comes to light. Couple this with developers’ unfettered ability to knock down multiple low-rise apartment buildings to make way for one very large urban mansion, aldermanic and NIMBY restrictions on density and zoning, and the picture becomes very clear.

We need more supply. And we need to preserve our existing stock of precious, naturally occurring affordable housing. Recent policies to allow for coach houses and accessory dwelling units (ADUs) and some density bonuses for those who provide affordable housing are a start, but our city politicians and constituents need to do a better job supporting density and supply as this is the only way we can truly address the housing affordability problem.

Naturally occurring affordable housing is one of Chicago’s greatest strengths and is the bedrock of workforce housing and home to many middle-income earners. The loss of this housing stock has had a catastrophic effect on our retail corridors and has in turn removed thousands of housing units (and people) from the overall supply pool. Combine that with the loss of tens of thousands of apartment units from 1970 through 2005, and there is no surprise that we have a supply side housing issue with extreme pent-up demand.

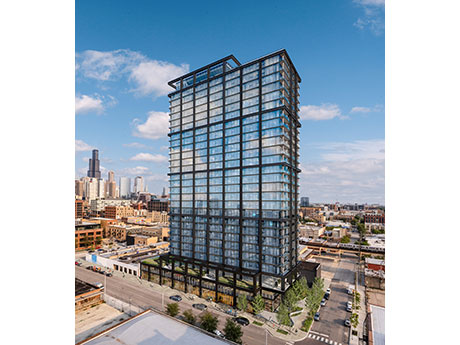

Further, due to the current cost environment, the only apartment product that is being built in the city is ultra-luxury or Class A housing that is very expensive. Most of the market cannot afford to pay $3+ per foot, and the cost environment has not shown any signs of relenting. This has put a spotlight on the above-mentioned naturally occurring affordable housing and has presented an additional argument for offering government subsidies or economic incentives to developers.

If our leaders could only refocus on the source of the issue, which is there is significantly more demand than available supply, then we would realize that providing tax abatements and other incentives to developers to encourage building more supply would have a much more significant impact than the current ARO or any rent control legislation ever has.

Moreover, if we are going to introduce government restrictions on housing in the City of Chicago, they should revolve around dissuading the removal of two- and three-flats from our neighborhoods and stop encouraging the building of large single-family homes in our dense neighborhoods across multiple lots.

As many states have focused on the demand side and rent control-based solutions to an obvious supply side issue, I would suggest that we lobby our municipal leadership to focus on supply side subsidies that have clearly worked for decades in other secondary markets. Real estate tax abatements, as an example, have been successfully used to spur development and affordable housing. They give developers an economic solution to the high cost of building affordable housing, while providing communities and municipal leaders with affordable workforce housing that is accessible to a larger and more diverse segment of our population.

Tyler Hague is an executive vice president with Colliers. This article originally appeared in the October 2022 issue of Heartland Real Estate Business magazine.