After massive bank runs earlier this month, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC) took the reins at two regional banks, Silicon Valley Bank based in Northern California and New York City-based Signature Bank. First Citizens Bank has since agreed to acquire the assets of Silicon Valley Bank.

According to the FDIC, 2023 already represents the largest year in bank failures in terms of total assets ($319.4 billion combined between the two banks) since 2008, when 25 banks failed (representing $373.6 billion in total assets).

“In a very short timeframe, we’ve now seen two of the biggest bank failures on record, the biggest one of course being Washington Mutual back in September 2008,” said Matt Anderson, managing director of Trepp, a New York-based data analytics firm. “We are in a very fraught period right now. Nerves are very frayed at the moment seeing two large bank failures in quick succession.”

The comments came during a Trepp-hosted webinar titled “Bank Turmoil and What it Means for CRE & Capital Markets” on Friday, March 24. The three-person webinar featured panelists Anderson and Dr. Stephen Buschbom, research director at Trepp. Lonnie Hendry, the firm’s senior vice president and head of commercial real estate and advisory services, moderated the discussion.

The consensus is that many banks around the country are reeling from years of investing in low-interest Treasury bonds, which have plunged in value amid the Federal Reserve’s nine consecutive hikes to the federal funds rate. The latest rate hike by the Federal Open Markets Committee came at its March meeting last week, increasing the federal funds target rate to a range of 4.75 to 5 percent, a 475-basis-point increase in 12 months.

With the Great Financial Crisis occurring in the not-so-distant past, the bank failures of this magnitude raised alarm bells throughout the capital markets. Part of the reason it’s such a shock is that banks have strict stress tests to ensure they can withstand mass withdrawals.

Anderson said that the stress tests banks typically utilize estimate losses of loans and not securities, though he expects that to change moving forward.

“Securities have been less of a focal point of stress testing in the past, but I can guarantee in the future that’s going to be added to the list,” said Anderson.

The panel agreed that liquidity will be a major point of emphasis moving forward in light of the recent turbulence. According to recent Trepp data, banks had $620 billion of unrealized losses in securities in the fourth quarter of 2022.

Even with the international banking requirements of having enough capital on hand to cover 30 days of average outflows — called the U.S. Basel III liquidity coverage ratio, a reform established in 2014 that stems from the Basel III accords set in 2009 — Anderson said that SVB would have still had issues as the bank endured withdrawals totaling 25 to 50 percent of its total deposits in one day.

“[SVB] was sitting on a massive amount of paper losses that were unrealized losses on the securities book,” said Anderson. “If SVB had to take all those losses at once, it would have wiped out all of the bank’s capital, so it would have been negatively capitalized.”

Debt hitting a wall, and a ceiling

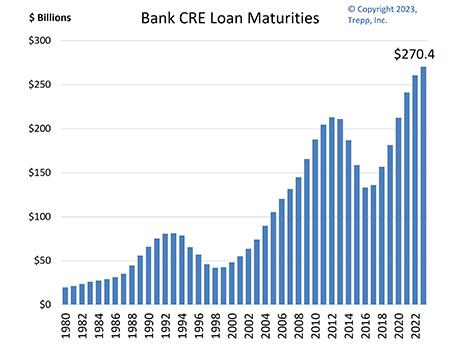

Trepp data shows that $270 billion of bank commercial real estate loans are maturing in 2023, which is an all-time record year for loan maturations. Anderson said that the figure isn’t too surprising since it’s a reflection of the overall growth of the commercial real estate originations market, meaning record levels of inventory of commercial real estate assets and overall pricing equates to more lending volume.

However, he said the proverbial debt wall is concerning because a high point in commercial real estate lending has been a precursor to recessions in previous economic cycles.

“In the late ’80s and early ’90s, we had a huge ramp-up in commercial real estate lending that ended in disaster,” said Anderson. “And then of course, the overshooting again in the Great Financial Crisis.”

Buschbom added that near-term loan maturities, or loans maturing in the next 24 months, that have a debt-service coverage ratio (DSCR) below 1.25 totals a little over $70 billion. He said that total is a big leap from mid-October 2022 when Trepp data showed that figure at $53 billion.

“Where are these loans going to find a home? The short answer is that if things hold where they’re at, some of these just won’t find a home,” said Buschbom. “It will end up looking very much like 2008-2009, where we are kicking the can down the road, just trying to work with the loan agreement that’s in place and try and work through the economic environment as it stands until we can get some sort of resolution.”

Of the loans with DSCR below 1.25, which generally represents a line of demarcation between low- and high-risk loans, a little over half of the loans are for multifamily properties. That property type has benefitted from a decade of robust competition from banks, agencies (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac), debt funds and life insurance companies, among other capital sources. With strong property fundamentals due to high demand for multifamily living, the competition among lending sources led to loans at higher risk of default.

Buschbom noted multifamily lending in particular could be handicapped in the coming months as the U.S. Treasury Department is approaching its debt ceiling. The Treasury won’t be able to fund any more debt to its agencies unless its $31.38 trillion cap is raised or suspended.

“Multifamily could be a little challenged when we enter debt ceiling issues in a couple months,” said Buschbom. Reuters reports that the Congressional Budget Office expects the Treasury to exhaust its resources by the third quarter of this year.

Office sector in a bind

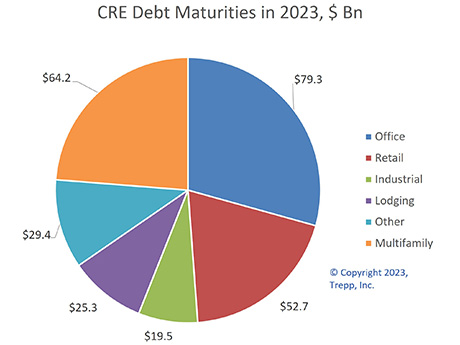

Of the $270 billion in bank commercial real estate loans maturing this year, about $79.3 billion (or 30 percent) are backed by office properties, the highest amount among all property types. What’s particularly concerning among the Trepp trio is the trough that the office sector is in due to the prevalence of remote work and flexible/hybrid work schedules in the modern U.S. workforce.

“Office loans are their own beast,” said Buschbom. “There are not many lenders right now that are looking to reach for yield in the office sector.”

The sentiment among lenders is reflective of market conditions. The United States currently has an office real estate inventory hovering around 5.56 billion square feet, and Cushman & Wakefield forecasts that the total will increase slightly to 5.68 billion square feet entering 2030.

However, the commercial real estate services firm estimates that the U.S. workforce will only require 4.61 billion square feet of office space at the end of the decade, assuming office-using employment grows by 6 percent over that period. If realized, the 1.1 billion-square-foot glut of excess office space will represent a 55 percent increase from the amount of obsolete office space in fourth-quarter 2019.

Hendry noted that there is variance from market to market when looking at the health of the office sector, but there’s undeniably softness nationwide.

“There is about 2 million square feet of sublease available in the office sector in Minneapolis,” said Hendry. “In New York, the number of office buildings that predate 1970 is astounding. It will be interesting to see if they are viable into the future, given the new environment that we’re in.”

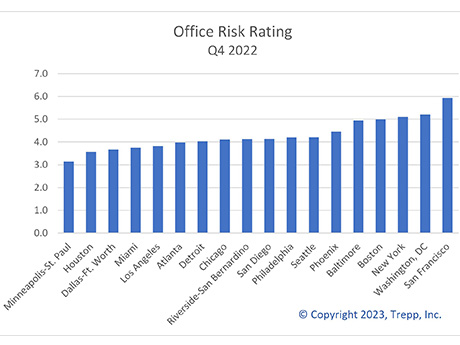

Hendry discussed Trepp’s Anonymized Loan-Level Repository findings for the office sector, which analyzes collateral attributes and loan performance over time from large and mid-sized banks. Trepp categorizes the level of “criticized loans,” or those with a numerical score of 6 or higher on its 1-9 scale, with 9 being a loan in default, by metropolitan area.

In these findings, the top three highest-risk office markets were San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and New York City.

“Those are typically gateway-type cities that are really struggling,” said Hendry. “As we enter this new paradigm with office, some of these ‘second-tier cities’ like Dallas and others may come out as a winner because they’re not as central business district-dependent. They have a little bit of a hybrid between the suburban and urban office footprint.”

— John Nelson